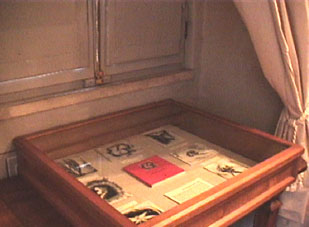

Related books

Italian language translation with original English text.

John Keats Percy B. Shelley

Book cover and drawings by Nancy Watkins

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Book cover and drawings by Nancy Watkins

Nancy Watkins

The publisher:

Il Labirinto

www.labirintolibri.com

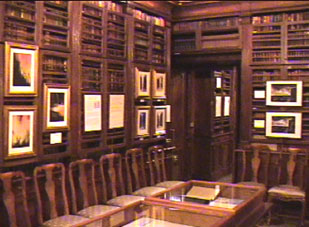

The Poet's Room Nancy Watkins Keats-Shelley Museum Piazza di Spagna 26, Rome, Italy |

|

from The Poet's Room exhibition catalogue

Duality: Painting The Poet’s

Room

An Inside Interview

Nancy Watkins

Why The Poet’s Room?

The Poet’s Room has long been a theme of mine—a

painting in my first solo exhibition years ago was called The Poet’s

Room—and I love the idea of exhibiting this series in the

very rooms where Keats briefly resided and died. As Baudelaire says

in his prose-poem of this name, the poet inhabits a ‘Two-fold

Room’. It has been my special privilege to catch firsthand glimpses

of the ordinary, everyday room in the act of its transformation into

the extraordinary one of poetry. The most seemingly everyday circumstance—Keats

walks outside and sits under a nearby tree—and off he is, on nightingale’s

wings, near and far in pithy musings. Italian catches this dual room

perfectly; the very word for room is ‘stanza’! Strangely

enough, I recently read that in Shakespeare’s and even in Keats’s

time, ‘Rome’ was pronounced ‘room’. So Keats

had a room in Room...

But you are a painter, not a poet.

Art and poetry are kin. At their best, I see them as a sort of intersection

of two ideal lines. One of the lines is vertical—it points upward,

uplifting the soul, feeding it with visions of beauty and the sublime.

To quote Schumann and Kandinsky, the role of art is to ‘send light

into the darkness of men’s hearts’. The other line is horizontal,

our horizon if you will. It tests our perspective and limits by giving

access to strong positive or negative experience. One can feel deep

horror, emptiness, love or empathy, protected by distance, by glass.

The art of every age has looked to other forms of art—music, poetry,

literature, dance—not to incorporate them, but rather to establish

a dialogue or a translation. For me painting must remain painting but

enrich itself with the rhythm, the truths and, yes, the colour of poetry.

|

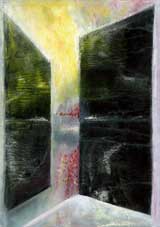

When these enchanted portals open wide, John Keats, ‘To my Brother George’

Entrance I, Acrylic, 24 x 17 cm © 2006 by Nancy Watkins |

|

Speaking of the two intersecting lines, a central

theme for you seems to be that of transformation. Being interested

in a subject’s dual nature, I particularly want to catch the moment

of transformation. Take, for example, the Entrance series.

The door cracks open, and the first, tantalising glimpse of what lies

beyond is revealed. The door creates separation, the entrance is an

initial space, a connection between inside and outside, between two

worlds. Furthermore, the word ‘entrance’ is both a noun

and a verb. The verb ‘to entrance’, to enter into a trance,

to be transported beyond the everyday, takes the simple noun ‘entrance’

to another level altogether. ‘To entrance’ is nothing less

than the often overlooked, but true role of art and poetry. In his remarkable

essay, Art as Mediator Between this World and the Other, Hector

Murena, ‘el gran olvidado’, examines the central

and sacred role which art was called to fill in antiquity—that

of mediating between the two worlds—and how art’s role has

changed over the ages, becoming ever more insignificant and marginalised.

The tragic part is that the irredeemable melancholy and nostalgia, the

‘sacred wound’ if you will, from which poetry and art spring,

are as present today as ever. What is hidden, denied, is the possible

role of art to link the two worlds. Where even a fairly modern poet

like Keats can write, ‘when these enchanted portals open wide

... the Poet’s eye can reach those golden halls’ (‘To

my Brother George’), for me the Entrance represents an

access, more or less forbidden, to these ‘golden halls’.

|

The last, whom I

love more, the more of blame John Keats, ‘Ode on Indolence’

Guardian Demons III, Conté, 25 x 18 cm © 1993 by Nancy Watkins |

|

The Guardian Demons series?

Often my titles play off a verse. In this case it was Keats’s

‘my demon, Poesy’ (‘Ode on Indolence’) that

sparked the idea of titling the series Guardian Demons. What

a threesome he creates with Love, Ambition, Poesy! Guardian Demons,

it goes without saying, echoes Guardian Angel. The word ‘demon’

is fascinating for its radical change in meaning over the centuries:

from its Greek root daimon ‘deity, genius’, to

the darker Latin daemonium, meaning ‘lesser of evil spirit’,

on to the rather generic and still familiar century-long use, ‘an

evil spirit or devil’, and that other parallel modern usage, trivialised,

certainly, but in some ways closer to the ancient Greek root, where

we can fondly say about an energetic child, ‘what a little demon!’

or even compliment someone on being a ‘demon cook’! Poets

often call back the root meanings of words, and I like how the original

Greek meaning of ‘demon’ works for the series in one way

and also the energy that the other meanings of ‘demon’ give

to ‘guardian’. Finally, think of Keats being driven by his

beloved demon Poesy!

The mysterious Hyerusch Mirror?

Ah the Hyerusch! Long has it captured my imagination with its unexplained

presence in the half-forgotten house, and the strange flames rising

from its cold mirrored surface. Here again the image comes from a poet,

in this case a short prose piece by Gianfranco Palmery. Does the Hyerusch

really exist? Is it an image from the other world, the one of dreams?

A metaphor of creative passion? All of these things together?

Many of your works have double names, Window-Mirror,

the Fire-Flower series, etc. Duality, as I’ve

said, is a central theme, but sometimes arrives on its own accord. In

Window-Mirror, I was interested in the view from a high rise

window and set out to do a simple exterior view. When I finished, I

looked at the work and was surprised to see an interior with a sort

of chair in front of a mirror emerge. And how symbolic to have the window

coincide with the mirror! Aren’t windows and mirrors really the

two main paths of knowledge? One needs the window, needs to interact

with the outside world, but just as important is to look deep inside

oneself, in the mirror if you will. True knowledge could be thought

of as an intersection of these two moments.

I see you have illustrated many books of poetry. It is true, I’ve

done many books, and book covers, most of them for poetry, but illustration

isn’t exactly the right word. Rather, as in this exhibit, it is

more finding a common spirit, points of contact. In fact, while I have

long known Keats’s poetry, even assisted in translating it, all

the works were done independently. However, often a few lines, like

those of Keats that I’ve used for this show, resound in my mind,

so there are also connections of which I am not consciously aware.

What are the points of contact for your Flower

series published in Amore e fama, translations of Keats’s

poems? Here we return in a literal sense to The Poet’s

Room. As Keats lay dying, among his few comforts were the large

white flowers with golden centers painted on his bedroom’s sky-blue

ceiling and his thought of the violets in the cemetery that he already

seemed to feel growing over him—unforgettable. Keats’s poetry,

of course, has many images of nature and flowers and the forget-me-not,

that together with the blue bell and the violet, is in the famous sonnet

in defense of blue, certainly has some relation to the flower that blooms

on the cover of Amore e fama.

|

Sprite of Fire, I follow thee John Keats, ‘Song of Four Fairies’

Fire I, Acrylic, 30 x 31 cm © 1998 by Nancy Watkins |

|

The last series of paintings in the exhibit is the one of Fires. Talk about transformation... I love to follow the alchemy of heat with its corresponding gradations of intensity and hue, and mutation almost complete—the deep red-trimmed black suddenly mellowing into a shimmering, and, an instant later, dull, grey ash—but still retaining for a moment more, that shadow memory of the original object. I have painted various series of Fires in their different moods: raging hot or slow burn, sparking with flashes of light, vertical or horizontal flames, fires as if from nature, from human-made objects, theatrical fires. I was delighted how precisely Keats’s ‘Sprite of Fire’ (‘Song of Four Fairies’) reflects their blazing light.

|

Nancy Watkins

|

|

To contact this author: autori![]() labirintolibri.com

labirintolibri.com